Markets are on the fritz and investor sentiment has slumped into “extreme fear” territory. Consumer confidence readings have cratered and surveys show a sharp turnabout in Americans’ feelings about their future financial well-being. Any positive reports are described by economists as the “calm before the storm.”

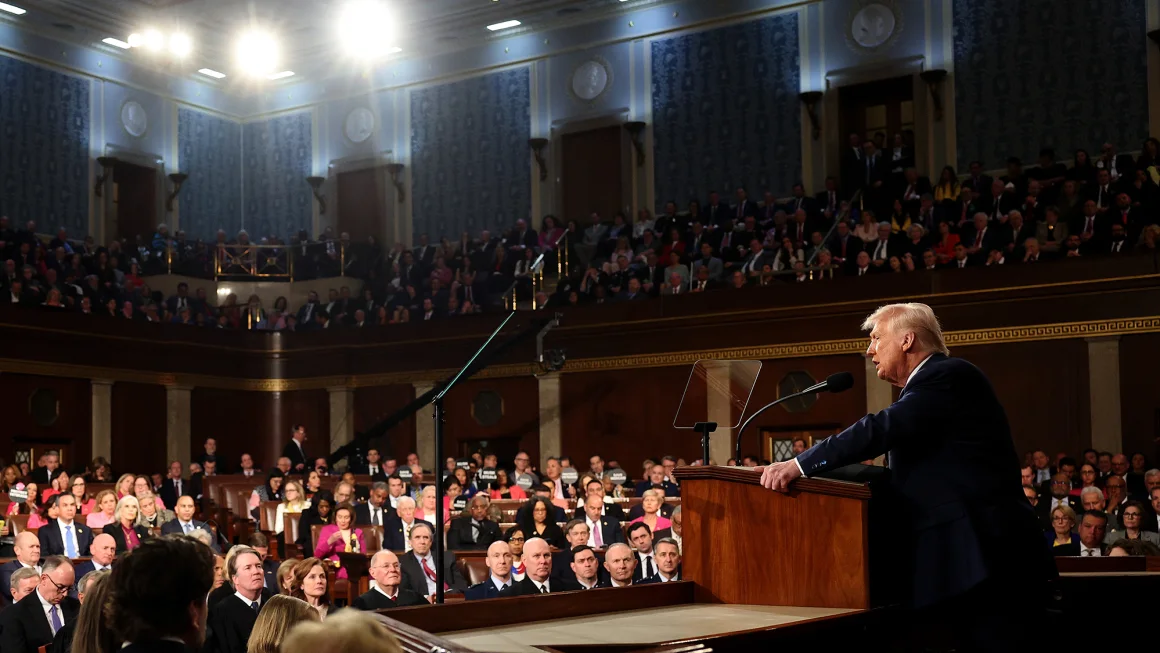

The common denominator is pure and utter uncertainty — particularly about just how President Donald Trump’s sweeping policy actions could shake out, economists say.

However, when the topics of the economy, volatile markets, shaken confidence and sudden recession fears have been broached with Trump, he’s hammered on familiar notes: That the Biden administration left him with an economic situation that was “catastrophic,” a “nightmare,” “horrible,” or “damaged.”

Still, data aside, the economy didn’t feel great to all Americans who suffered through the highest inflation in decades, and those sour feelings helped send Trump back to the White House for a second term.

Such claims have become a hair-pull for economists, statisticians, academics and fact-checkers alike: By most gold-standard measures, President Joe Biden handed Trump a booming economy. And, if anything, the economy was ripe for a resurgence in early 2025 under Trump.

“The economy was bad under Biden and that was reflected in the polls last year; but inflation and every other economic indicator had more or less stabilized when President Trump took office,” Jai Kedia, an economist and research fellow at the Cato Institute.

Kedia said, is a tale as old as politics: The blame game.

Kedia, who’s a Libertarian, is in the camp of politicians should “leave things alone,” when it comes to the economy.

“This is true in the Biden administration with the massive spending bills and all of that, which in some part led to inflation; and that’s true now with the tariffs that we’re seeing,” Kedia said. “It’s really hard to figure out why you would blame the previous administration. The stock market actually went up once Trump was elected, and it’s only in the past month when the administration is playing around with dangerous economic ideas that you see the economy started to swivel back.”

“That’s a direct result of the tariffs and other economic proposals,” he said.

There are plenty of caveats when it comes to economic data: One month does not make a trend; figures are preliminary and often subject to revision as more detailed information becomes available; reports often represent a snapshot in time and can be influenced by one-off events such as weather; and, above all else, it takes time for situations to evolve and be fully understood.

“This is a problem across our political spectrum of cherry-picking one month of employment or inflation reports to make general conclusions about the trend,” Kedia said.

Take, for example, Biden taking credit for “creating” nearly 16 million jobs during his time in office; and then, most recently, Trump touting a slice of the February jobs report: a 10,000-job boost in manufacturing that he credited to his tariff-heavy trade policy and desires to make America a factory superpower.

Both claims have truthful elements to them, but there are important distinctions to be made: For Biden, he needed to clarify that it took roughly 9.5 million jobs of those to get back to pre-pandemic levels of employment; and for Trump, those gains are preliminary estimates and very well could be reflective of investments put forth under the Biden administration.

“It’s way too early to understand what the effects of the tariffs are on manufacturing and the rest of the economy,” Kedia said. “The markets clearly are telling you where they think this is going.”

This and other alarm bells are heightening recession fears.